Ferdinand: Our Childhood Queer Icon

Queering Ferdinand

The choice of working with Munro Leaf’s The Story of Ferdinand (1936) was initially due to personal experience of the text as a child. I identified with the little bull that did not want to play rough and who liked to sit quietly under a tree instead, who is accidentally chosen for a big bullfight and when taken to the ring in Madrid, does not fight the matadors but sits and smells flowers until he is taken back to the wild. In creating the work, I recognized a unique kind of engagement with the text which made me reflect that personal relations to texts we have identified with, or perhaps have been silenced in, can fuel creativity and offer the adaptive possibilities of positive world-making, where we try to fix a past in which we’ve been wronged.

Ferdinand’s status as a worldwide classic in children’s literature (Steig 118) was also a factor in its selection, due to Hutcheon’s notion of the pleasure of recognition (108), and its potential to reimagine well-known heteronormative worlds into more inclusive spaces. The text has experienced two popular adaptations: Disney’s 1938 cartoon, Ferdinand the Bull, and Carlos Saldanha’s 2017 animated movie, Ferdinand. Both adaptations focus on Ferdinand’s pacifist tendencies, and none on gender identity (although Disney’s Ferdinand moves with a slight strut in his trot, and is voiced in a shrill manner that hints, concerningly, at judgement against effeminacy). This presented us with the creative thrill of uncharted territory.

The Story of Ferdinand has a contested history of criticism that made it an exciting text to work with. From a new historicist perspective, Steig highlights Leaf’s other literary production: a considerable collection of conduct books produced in the thirties, which Steig believes are “exercises in making conformity acceptable” (118). If we consider Ferdinand within this corpus, Leaf’s work, beyond the essential education of children, could be reflective of a wider need to conform within the ideological machinery that would implement itself in America shortly after Ferdinand’s publication, and that was fuelled by events in modern American history: post-Depression capitalism, World War Two, the fear of communism or civil rights movements. Along this train of thought, we could read the fact that Ferdinand refuses to fight the matador as a call for passivity and indoctrination of children at a time when America was experiencing civil and political unrest.

Other interpretations, Steig further contributes, criticise Ferdinand’s mother, the cow, for “suffocatingly trying to keep [Ferdinand] in childhood forever” (119) and avoiding his male, aggressive responsibilities; the absence of a father figure has been duly noted as a cause for Ferdinand’s feminization (119); and in his sit-down strike at the bullring, Ferdinand has been considered a symbol of civil rights and Apartheid movements (Martínez 28), as well as a parody of the sixties’ “flower children” (29). That a little bull causes so many contrasting interpretations posits Ferdinand as a queer figure: his mere existence and way of being escaping normative classification and inciting such vehement criticism is, I believe, something very relatable to young queer people.

My queer analysis of the text was a dialogic process between the text, queer theory and in-studio analysis with the performers. After multiple sessions discussing the text, we identified several elements that offered creative challenges when adapting, and which would best portray the concepts of nonnormative gender identities. These were the idea of animals as queer allies; queer spatiality; the conflict between wildness and domesticity; and the characters of Ferdinand’s mother and the antagonistic matador.

Animals, in most contemporary societies, are generally other, and their otherness is one that children relate to very easily (Halberstam 145). In Western society, we are culturally programmed to understand the animal fable as a didactic tool from an early age, so working with a text that included animals offered a more direct connection with young subjectivities. In terms of exploring queerness, animals are a particularly good allegory because of their relation to nature, and how this translates to the historical collocation of queer identities and desires as against nature (Alaimo 52). The Story of Ferdinand, like many other texts for children, makes a clear distinction between the civilized world and the wild. As a bull, Ferdinand belongs to the wild. Yet within the society of bulls in the text, he is othered further: “All the other little bulls he lived with would run and jump and butt their heads together, but not Ferdinand.” In a sense, whilst being within nature, Ferdinand is also against nature.

Halberstam characterises the relationship between queerness and the wild as the following:

The gender-queer subject represents an unscripted, declassified relation to being- s/he is wild because unnamable, beyond order because unexplained; s/he…[is] part of nature, but unexplained (23).

While the first few pages of the story have Ferdinand nestled amongst flowers, when he accidentally sits on a bee- “Wow! Did it hurt!”- Ferdinand “ran around puffing and snorting, butting and pawing the ground” by accident, moving just like the other bulls do. This sequence of events queers Ferdinand. Sat by his tree, he is othered within the wild, yet he is also capable of displaying the taurine behaviour of his peers- effectively “passing” as male; so much so that is he chosen for the bullfight. This range of behaviours challenges categorization of what bulls and cows do, and neither the other bulls nor the matador can explain what Ferdinand is. That Ferdinand navigates these identities “defies the regimes of regulation and containment that shape the world for everyone else” (Halberstam 23).

Because of Ferdinand being clearly placed within the natural world- hills, forests, flowers- animals like him can further elucidate trans resistance and identities, as defended by Stryker. The many moments of Ferdinand sat by his tree could illustrate her notion of a body that is “within nature but against nature” (248), as we don’t generally see bulls, or culturally relate them to, smelling flowers or dallying with butterflies. Most Western associations with bulls are masculinity-led, signifying ideas of power, virility and reproduction. That this highly encoded and gendered animal is placed within a system of signifiers that opposes such allusions to virility allows Ferdinand to embody trans and queer resistance in an effective way.

Another interesting concept in the text was the idea of domestication. We understand that acceptable animals are those that can be domesticated into human structures of behaviour. A concept not too distinct from the education of children, who to be accepted in society, must learn the behavioural structures of dominant discourse, which in Western society, Halberstam defends, is that of white heteronormativity (145). When Ferdinand is taken to the bullfight in Madrid, “he wouldn’t fight and be fierce no matter what they did.” He remains a towering yet peaceful figure coloured white, against the red and raging images of the banderilleros, who flutter around him in frustration, all of them trying to “domesticate” Ferdinand into the cruel brutality of bullfighting (and masculinity). Ferdinand’s peaceful refusal of domestication not only illustrates Alaimo’s thinking that “queer animals elude perfect modes of capture” (67), therefore offering a great metaphor for queer resistance, but also, that the challenge to animal domestication in children’s literature “calls the conventions of so-called civilized animals into question” (Halberstam 145), considering the fatal consequences Ferdinand would have experienced had he accepted his gendered domestication.

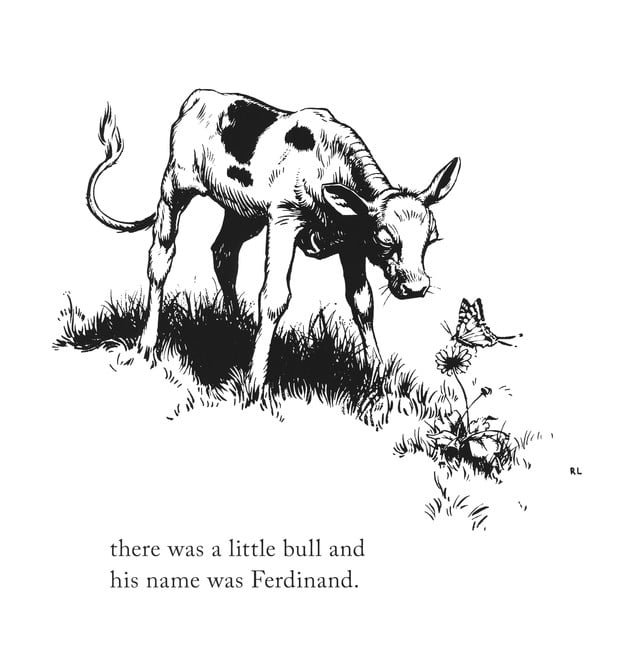

Halberstam’s investigation into queer wildness is also concerned with the wild as a space. Building on cultural identifications of the wild as a site for danger and unwanted sexual maturity- exemplified by the Western fairy tale canon and challenged in contemporary literature by authors like Angela Carter- Halberstam questions the wild as “the other to the home or the zoo,” which “can only be a place of ruin and sadness” (145). The Story of Ferdinand, mostly through its pictorial elements, reimagines the wild as a safe, subjective queer site through its clear comparison of natural and urban spaces: when Ferdinand is in the wild, the visual signifiers are context-related to calming emotions: flowers, butterflies, shaded trees, unlike the oppressive imagery of the city. Robert Lawson’s illustrations, as Martínez points out (35), make an interesting hermeneutical use of close-ups and longshots. Although several longshot illustrations of Ferdinand at his tree could illustrate the isolation of queer subjects, when he is in the wild we are offered several adorable closeups of him smelling flowers or calmly watching the world in front him. The closeness can be read to celebrate individual subjectivity, speaking to young readers of the value of independent thought.

By contrast, when Ferdinand is taken to Madrid, the majority of illustrations are longshots. Driven to the city in a cart, Ferdinand looks awkward and small as he is dragged by donkeys along a towering bridge; citizens high up in their balconies watch as his procession drives past, and in the bullring, through the archways of a huge staircase, “all the lovely ladies had flowers in their hair,” but here, rather than peace, flowers could signify something more sinister as most of the women’s faces are hid behind red veils or fans. In fact, in most urban spaces, Ferdinand is constantly observed from around and above, by almost faceless people. They have expectations and demands concerning Ferdinand, and they also fear him. This could be a poignant allusion to the societal pressure experienced by trans and queer folx in a society that has very clear requirements of gender, a pressure that the wild and its queer spaces alleviates.

The story’s main adult characters also lend themselves to queer analysis. Ferdinand only interacts with two adults: his mother, “who was a cow and would worry about him” as “she was afraid he would be lonesome;” and the “the Matador, the proudest of all.” These two gender-polarised characters can be read as parental figures, in a paradigm that is reflective of parental structures experienced by many queer folx. On the one hand, we have a female energy that facilitates and is accepting: “and because she was an understanding mother, even though she was a cow, she let him just sit there and be happy” (although we could find the apposition somewhat gender-troubling). Through her we recognize the stereotype of the benevolent and peaceful mother. On the other hand, we have a matador who is full of bravura and gender expectations: he embodies the stereotype of the stoic, disciplinary father, who must teach his child to follow the rules, whose pride is at stake if they don’t. Although my interpretation is in itself binarized, and assumes that all queer subjects have two parents, this paradigm of acceptance and facilitation versus opposition and discipline is one that many of us queer folx have experienced, regardless of what parent or carer performs either role, and therefore the text in this sense is representative of queer experience. What is wonderful about The Story of Ferdinand is that Ferdinand does not “accept the wisdom of grown-ups” (Nel 476), to empowering effects.

Creating The Bull and the Moon

The Bull and the Moon is a children’s dance theatre production created in 2021 for DeNada Dance Theatre, with performers Anna Álvarez and Dominic Coffey. Set in 1930’s Spain, and structured along the format of a bullfight, with four distinct rounds (and their “entre’actes”), it tells the story of Lolo, a little bull that loves flowers and is scared of bullfights- especially of Rosario the matador. Every night, he watches with admiration as the Moon dances and sings flamenco, and soon discovers that he identifies as Lola, a flamenco dancing cow.

When I approached adapting The Story of Ferdinand, one of the things that concerned me the most was the perceived parental binary of the text, in its depiction of female facilitation and male oppression. I was inspired by this to unify these shifting stances into one person, who clearly demonstrates that fear and encouragement are natural to all, and are not gendered emotions, creating the double role of Luna Flores / Rosario the Matador with performer Anna Álvarez.

Mother cow became Luna, the moon- an addition inspired by popular Spanish song by Carlos Castellano Gómez, The Moon and the Bull, that narrates the story of a bull that is othered for his infatuation with the moon, as well as by cultural connotations of the moon as a guiding light and of night as a safe space for queer dreaming. When developing the characters in the studio, we improvised through moving in space with the physical characteristics of the character (downward weight and broad chest for Rosario, undulating arms and spiralling back for Luna), playing along a scale of exaggeration in the amplitude of the movement. The higher registers of exaggeration became very interesting, not just because of the visual demands of street performance, but also because its campness “could easily be interpreted as the symbolic realization of an extroverted strategy of resistance” (Gere 356).

While analysing the movement of the role, I understood that both characters were resisting gender conscriptions. The character research for Luna was largely Spanish music icons such as Lola Flores and Rocío Jurado: larger than life women who broke boundaries in Spanish culture through their often wild performances, the subject matter of their songs, and their unabashed expressions of female sexual desire. Both of them are also often embodied by female impersonators in the Hispanic world. I asked Anna to play them as a drag queen would. Female impersonators in Spanish culture have historically been both a phobic and fetishized object, but drag is also a performance many queer children enjoy embodying, and are often bullied for- the dancers and myself included. Through the character construct of Luna, as Muñoz posits, “the phobic object, through a campy performance, is reconfigured as glamorous…and not as the abject spectacle that it appears to be in the dominant eyes of heteronormative culture” (3). In glamorizing drag, and signifying its performativity as benevolence, we disidentified with the homophobic stereotype and offered a positive light to nonnormative gender performances.

Rosario too was performed in drag, not so much in her performance quality, but literally, in that a cis woman dresses in an outfit, and carries out a role, traditionally reserved for men. Julian Pitt River’s introduction to the history of bullfighting offered us an interesting backstory: that of Teresa Bolsi (114), one of the first female matadors who struggled to be allowed into the bullrings due to her gender, and performed mostly as a sideshow. Inspired by her story, we thought of Rosario’s aggressive gender performance as a means of resisting patriarchal discourse, and reflected that while paternal figures can appear oppressive to their children, the parent’s own gender troubles have to be considered, which could inspire more empathy and understanding between family members. Through the creation of this double role, adaptation allowed me to de-binarize traditional gender structures through combining them into one performer, who played two characters but was visibly the same person, just as one parent or carer can feel opposing emotions.

In terms of developing the character of Ferdinand- in this adaptation, named Lolo/Lola- I was inspired by Muñoz’s idea of identity as work-in-progress, “a process that takes place at the point of collision of perspectives” (6). Many of the games we played in the studio were concerned with images of constructing gender through props and costume, and many of these were choreographed into the performance. The forbidden shoes scene is an example. Lolo is gifted a pair of flamenco heels by Luna; once he’s alone, every time he tries to touch them, an animal sound scares him away. One of the most popular scenes according to audience feedback, it portrays Ryan and Herman-Wilmarth’s idea of how desire is gendered from an early age (156): boys are not generally encouraged to wear heels. As his desire for the shoes grows, so does the cacophony of animal voices dissuading him from wearing them- illustrating the dichotomy between individual subjectivity and societal constraints we identified in the text. When he finally wears the shoes, the society of animals is silenced, and thanks to the heels and the wild footwork he can do with them, Rosario is scared off in her second attempt at fighting him. What child and adult audiences highlighted were the relatable struggle between desire and social imposition and the empowerment of self-construction.

When investigating how Lolo/Lola moved I realized how much gender is policed through movement from a young age, as David Gere explores in his study on effeminacy. Girls are taught to cross their legs when they sit, boys should not angle their arms and break their wrists because a broken wrist “implies weakness…serving as a visual metaphor, perhaps, for a broken weapon” (357). This realization inspired me to explore Lolo/Lola’s physicality through the movements that boys are generally forbidden to perform, as a challenge to normative language codes.

We created a scene in which Luna teaches Lolo how to dance flamenco, through demonstrating wrists and arm movements, clapping, and footwork. In the scene Lolo breaks many codes: as an animal, he learns a human dance, and as a male, he is also taught how to bend his wrist, sway his hips and dance with heels, all movements Western-coded as female. As Lolo rehearses gender, he is willing to discover himself in the movement of the Moon that he so admires. Finally, with the help of the audience- who are also encouraged to perform the movements- he breaks all codes and the resulting solo is celebratory and empowering. He “identifies with women…not as female impersonation but as tools in the performance of the ‘not male’” and effectively “demands-and wins- freedom from bodily restrictions” (374).

In developing this scene, I was troubled by the problematic of domestication of queer animals I had encountered in the text. I wondered if Luna’s “domestication” of this animal into the highly stylized language of flamenco could be read as the moment when young people “enter the realm of work, compliance and docility,” after which “they also give up another space: one governed by wild emotions, rebellion, and refusal” (Halberstam 128); if in learning flamenco, Lolo would lose the wildness we had signified as queer and diverse. It was important for me then, in directing Dominic Coffey, to emphasize the joy of learning this code, and also to show him rehearsing and practicing it, resonating with Judith Butler’s notion of gender as repeated performance (2497). In doing so we portrayed the agency of gender definition: Lolo chooses not to perform the movements Rosario demands of him, and instead decides to learn the dance that Luna shares with him.

It is through learning this physical language, and Luna’s gifts- heels, a fan, a flamenco shawl- that Lolo finally becomes Lola, the flamenco dancing cow. The final round of the bullfight sees a reversal of the roles in which Rosario charges headfirst at Lola, whose exuberant and wild dancing eventually exhausts Rosario into acceptance: the matador offers her the final touch to her outfit, a big red rose to place behind her ear, as a token of peace. Lola’s agency in her gender construction suggests that gender codes can (and should) be transgressed for the honest expression of subjectivities. And for those who have been bullied for being perceived as effeminate, the scene could help to heal in understanding that effeminacy is “a fundamentally defiant activity” (Gere 367), and that there is nothing more empowering than dancing to one’s own tune.

works cited

Alaimo, Stacey. “Eluding Capture: The Science, Culture and Pleasure of ‘Queer’ Animals.” Queer Ecologies: Sex, nature, politics, desire, edited by Mortimer-Sandilands, C and Erickson, B., Indiana UP, 2010, pp. 51-72.

Butler, Judith. “Gender Trouble.” Selections. The Norton Anthology of Theory and

Criticism, edited by Leitch et al, W.W Norton and Company, 2001, pp.2485-2490.

DeNada Dance Theatre. “Audience Reactions for The Bull and the Moon.” Vimeo, uploaded by DeNada Dance, 7 September 2021, https://vimeo.com/604331519/60d6eada2e

Gere, David. “29 Effeminate Gestures: Choreographer Joe Goode and the Heroism of Effeminacy.” Dancing Desires: Choreographing Sexualities On and Off the Stage, edited by Desmond, J., U of Wisconsin P, 2001, pp. 349-385

Halberstam, Jack. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Duke UP, 2020.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. Routledge, 2012.

Leaf, Munro. The Story of Ferdinand. Illustrated by Robert Lawson, Faber and Faber, 2017.

Martínez, Mateo. “The Story of Ferdinand: from New York to Salamanca.” Ocnos, 12, 2014, pp.25-55

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. U of Minnesota P, 1999.

Nel, Philip. “Children’s Literature Goes to War: Dr. Seuss, P.D Eastman, Munro Leaf and the Private SNAFU Films (1943-46).” The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2007, pp.467-487.

Pitt-Rivers, Julian. “Un Ritual de Sacrificio: la Corrida de Toros Española.” Alteridades, vol.7, 1997, pp.109-115.

Steig, Michael. “Ferdinand and Wee Gillis at Half-Century.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 14, 2009, pp.118-123.

Stryker, Susan., “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage.” The Transgender Studies Reader, edited by Stryker and Whittle, S., Routledge, 2009, pp.244-256.